Beside the Pointed

2020

Collaborative work created with fiction writer Jacob D. Wilson for week long residency with

Murze’s (now For All) online IsoArt Fest.

“...there in the midst of unfolding, with every new revelation, we realized that a belief we assimilated yesterday—today, no longer holds true.”

- Jacob D. WilsonDuring second week of May 2020, we have contemplated the nature of the rhetoric surrounding the Covid outbreak, how even as we sequestered ourselves in our homes, isolating ourselves from social situations, somehow the weight of our friends desires and our communities fears seeped into our homes.

Perhaps it was simply the shift in expectations or the creation of new social dynamics that disturbed us: six feet of space here, to wear or not to wear a mask, the reality of all these new social obligations creating a new paradigm that has shifted our awareness to the reality of the uncertainty of our speech. That, there in the midst of unfolding, with every new revelation, we realized that a belief we assimilated yesterday—today, no longer holds true.

Perhaps it was simply the shift in expectations or the creation of new social dynamics that disturbed us: six feet of space here, to wear or not to wear a mask, the reality of all these new social obligations creating a new paradigm that has shifted our awareness to the reality of the uncertainty of our speech. That, there in the midst of unfolding, with every new revelation, we realized that a belief we assimilated yesterday—today, no longer holds true.

studio

explorations

explorations

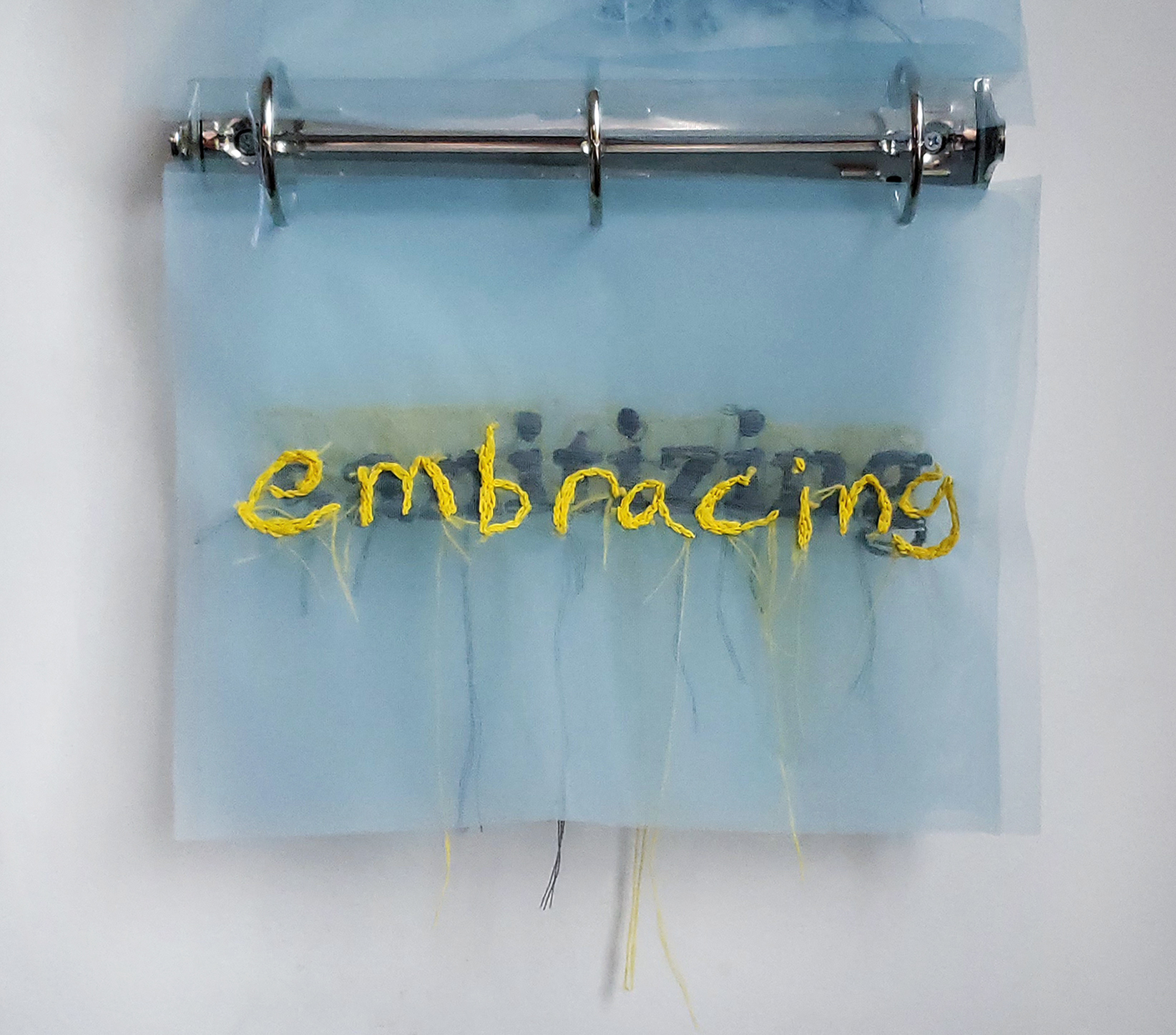

Receptacle (Dwelling)

layers of fabric & thread, 3-ring binder2020

[sold]

Tell us a bit about yourselves, your background.

Stacy: We live in Moscow, Idaho, a small town in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. I’m a mixed-media artist, primarily creating in 3D and an Associate Professor of Art + Design at the University of Idaho with a passion for dancing and 80s power ballads. Jacob, I call him Jake, is a writer I picked up at a bar in town last year.

Jacob: I rarely go to bars anymore, but, when I do, I find myself picked up and pocketed. I graduated from the University of Idaho’s MFA program with a specialty of fiction in 2019. I have a bit of an obsession with the craft of writing, a passion for ice/rock climbing, and a fondness for all -isms, -ists, and manifestos.

How has the pandemic affected you, your artwork and day to day?

Jacob: Honestly, although it feels weird to say aloud, in terms of my writing process, the pandemic has actually been a bit of a blessing in disguise because it’s provided me with ample time to write. After losing my substitute teaching gig due the school closures, I went back to work revising a collection of short stories. I’m so far into the voices, narratives, and ideas in these stories, that they don’t really allow the contemporary me in, so, it’s a bit like time traveling back to a pre-covid reality, which is a nice respite for a few hours each day.

Stacy: I’ve had respite too; I’ve been on sabbatical since January. As a professor, finding any chunk of time for studio is refreshing, so I was sure these five months were to be exponentially more serendipitous. But since covid popped my sabbatical bubble, I’m battling even my sewing machine. Just being near it used to feel soothing, but now whenever I’m not making masks, it guilts me. My creative resolve fractures. I stop making. Attempts at simple productivity while quarantining with Jake—planning meals, exercising, sharing books, etc.—and my week-day calls with my graciously forthright “art accountability buddy,” is helping me reconnect with my elusive sabbatical-self.

Tell us a bit about your work. What themes do you pursue in your work separately?

Stacy: Recently, my solo work has dealt with shifting justifications of our boundaries—both physical and personal—especially as they become distorted or lost. You can see this in works like my mixed-media wall piece series Shedsor my installation Dislocation Shifts. Consumed by modern distractions and environmental losses, so much of our lives seem to rush by, yet there is also an atmospheric desire to ground ourselves. I’m inspired by collapsed architectures, tight living spaces, upholstered furniture and the bits of nature and navigation you can find right outside a home—tree branches, gardens, stones & weeds, welcome mats & sidewalks. I enjoy the strange familiarity and poetic weight of colliding forms to capture complex personal navigations.

Jacob: I like the themes in my work to rise organically from the narrative itself. What really interests me is the reader’s experience, because without a reader a story is inert, lifeless. It is a minor distinction, but one I value highly, that is, I view storytelling not as a means of transmitting a character’s life, or philosophical ideal, or a political message, but as means to engage experientiality within the reader. I believe that even story is secondary to this, that every craft decision must serve not the artificial construct of language & narrative, but the visceral experientiality that language creates within the body and mind of a reader.

How have you changed your working process during the pandemic? What became your method of working together?

Stacy: When I came across the Isolation One Digital Residency with Murze Iso Art Fest, I saw it as a nice distraction from my canceled residency in Macedonia, a way to re-center my creative focus, and an opportunity to work with Jake for the first time: #isolatedbutnotsolitary.

Jacob: For me, writing has always been a solitary act. This was my first collaboration and learning how to let another voice into my practice was a wonderful and challenging experience. It took Stacy hovering over my shoulder and asking “what are you thinking” for the third time for me to realize that I didn’t actually know what I was thinking. That in order for me to express an idea, I need to translate from the discordant ideas, vague images, prosody, and the potentiality of emotion into language. Until that process is complete, I don’t, consciously, know what the hell I’m talking about, and learning to let Stacy into that stage, the intuitive process, felt a bit like having someone stumble around the dark and cluttered crawl space of my unconscious mind. To be honest, it was a bit invigorating.

Stacy: While Jake adapted to collaboration, I dealt with opening up my studio space to someone else. Since the lockdown, I’ve given myself the constraint of working only with the materials already at home or in my studio. Before I invited Jake into my studio, I created a pile of untouchable materials that were off limits. It made me uneasy at first to see him rummaging through parts of previous works. I had to fight my initial “No f’ing way”s and “I can’t use that again”s. It was a bizarre editing process of making do. The lack of familiarity with my work, his fresh eyes, so to speak, offered a potential for reseeing. His new perspectives, and physical presence, defamiliarized my process and allowed space for fresh constructions to begin.

What themes evolved as you began working together?

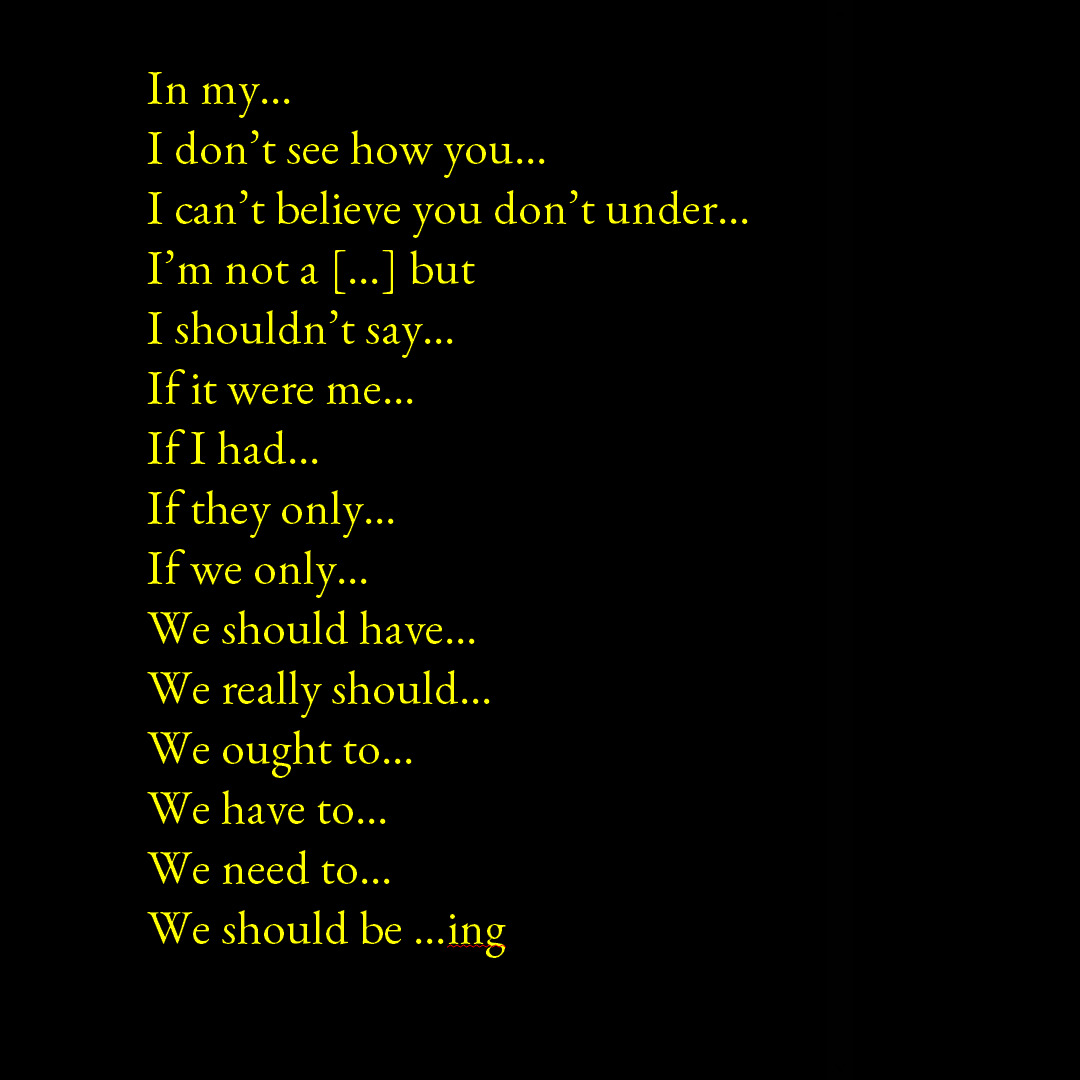

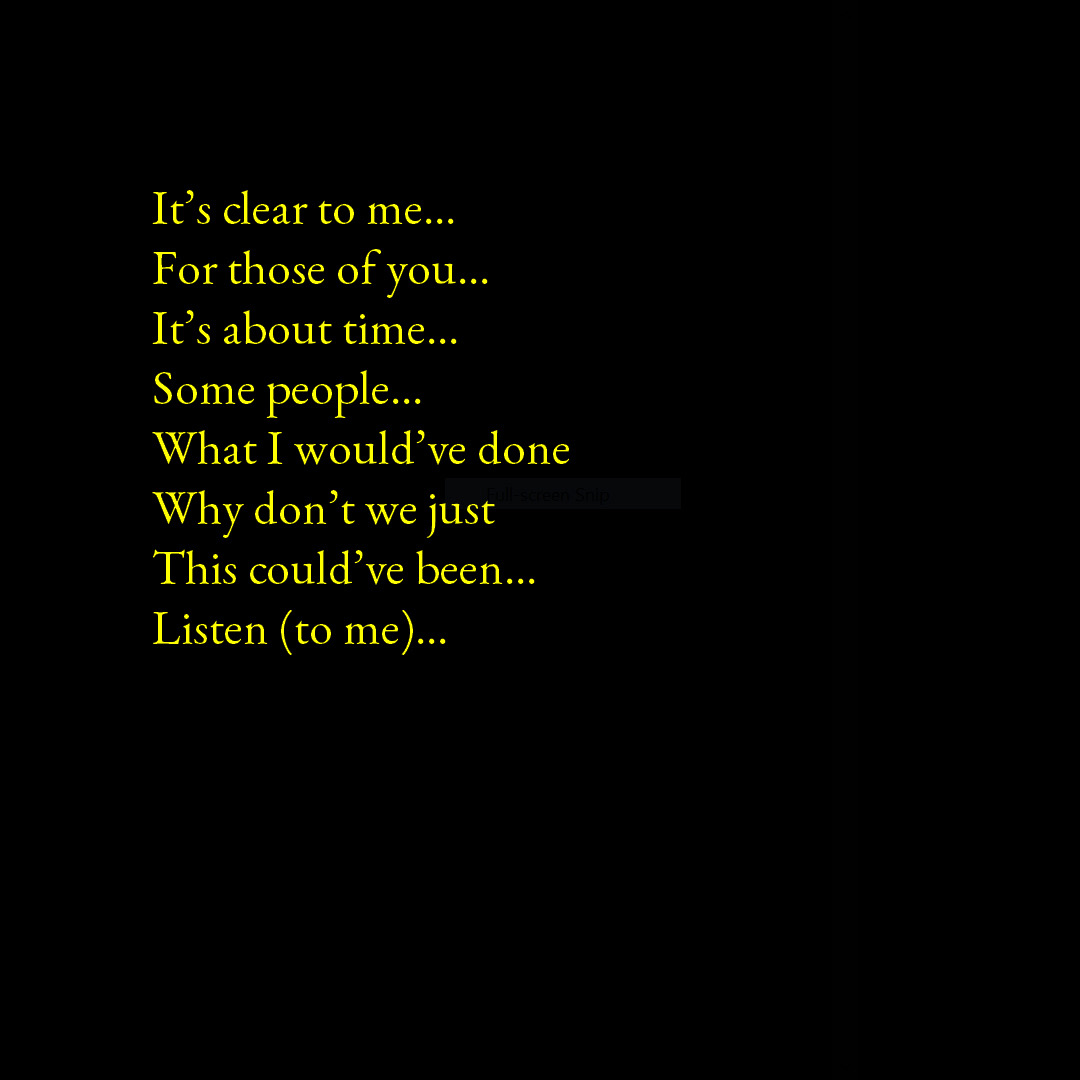

Jacob: Stacy and I spent a lot of time discussing the rhetoric of Co-vid. We were struck by how, even in a clearly uncertain crisis, people’s responses seemed to be spoken with certainty. They seem to be stockpiling present participles, bombarding us with “ing” words, dwelling on every breach of the new social contract, assuming the role of expert, and even weaponizing shame.

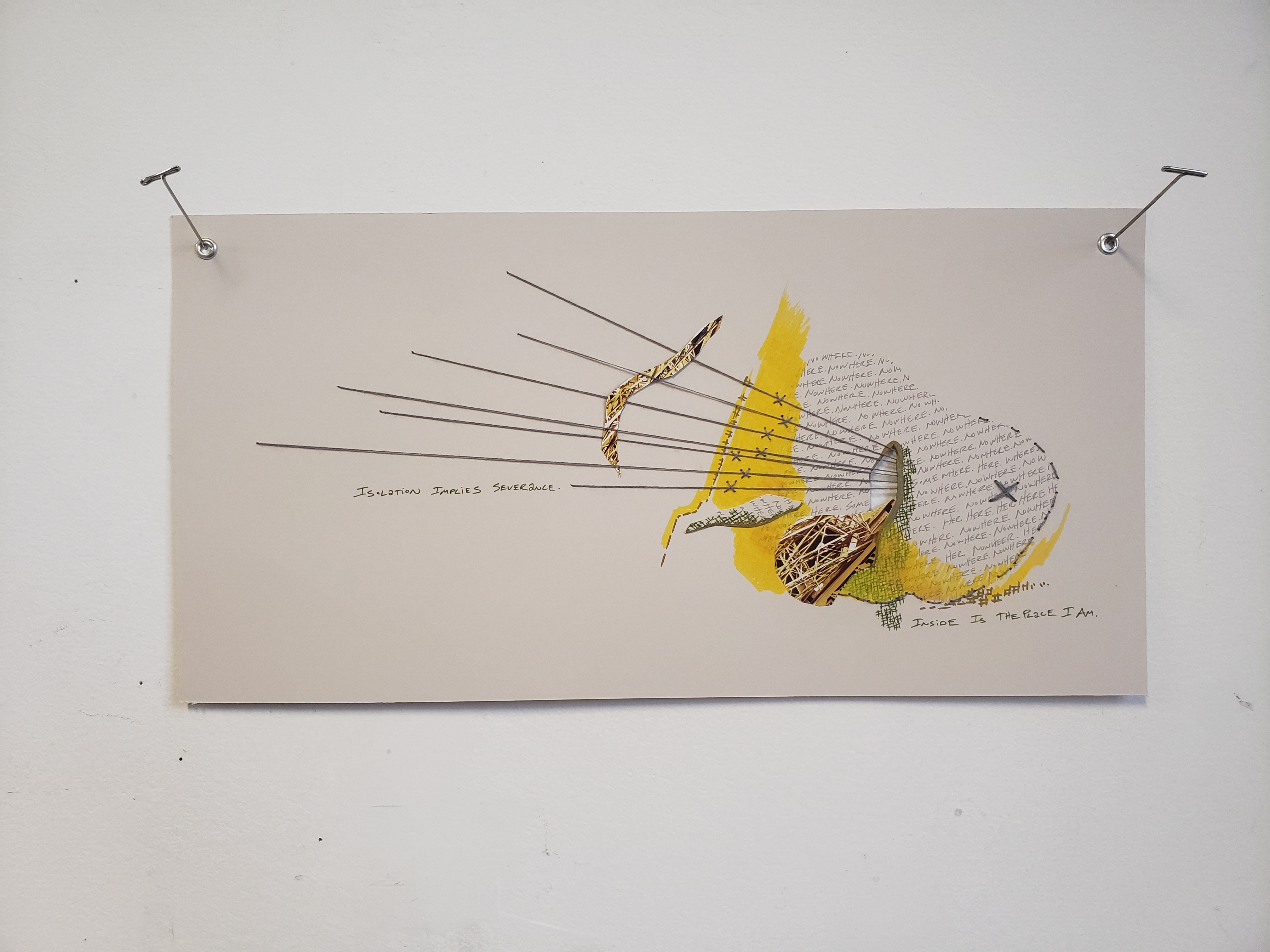

Stacy: Interested in the idea of trying to catalog all these floating yet tangled “ing” words, I began stitching our growing list of weighted words onto light blue sheets for what we are now calling Receptacle (Dwelling). It is a work in progress that will most likely grow into more sets of 3-ring bound word groupings. We also played with other display iterations of text on fabric strips. This process led to the blue spinal form in our installation.

Jacob: Stacy had a simple, free-standing steel frame, about as tall as a door, and just big enough for a person to step through. We shifted cinder blocks, shuffled metal frames, and weaved metal netting made from bed springs around the threshold. Stacy found meaning in the spatiality of the relationship between objects and I built a narrative with them, yet we couldn’t connect with each other’s vantage points. That is, until Stacy referred to the piece as a “persona”, and that’s something I understand, that’s character. I suggested we take a page from Gilbert Sorerentino’s novel Aberration of Starlight. We created a speaker with a series of questions: what they remembered from X event in their life; on what foundational memory was the character’s personality constructed, etc. We constructed our vague persona’s backstory, and suddenly, we had a speaker to contend with knocking at our steel threshold.

Stacy: We returned to physical construction, adding old pointed wood forms from my What Man Builds, Man Can Confuse series. They became the spine, the spewed expectations, and pointed fingers. As a net or cloak or cape or frozen conveyor belt, the metal mesh and blue fabric systematically projected our ideas into space, but now, in sync, the making flowed. We are now calling this installation, Beside the Pointed. We envision it standing among a mass of text imprinted onto the walls around it. Tangled “could”s, “would”s and “should”s, misplaced expectations, will become the atmosphere for what we have now while our Astro-turfed “ing” can act as a ground for more problematic projections to land.

Is there something you couldn't live without in your studio? What is your most essential tool?

Jacob: Solitude and coffee.

Stacy: And lucky for him, I’m here to challenge him on that first one... Without a variety of needles and thread, I’m twitchy.

What do you feel the role of visual artists and writers is in society?

Jacob: I’ve always been partial to Ezra Pound’s idea that the artist is “the antenna of the human race.” Like the chitinous antenna of an ant, I think the artist’s role is to perceive the world without judgment, to try to see the world, not as absurd or systematic, but simply perceive it as it is. To see beyond cultural/political/social white noise, beyond the systems that we inhabit and inhabit us, because, in the end, the contemporary systems that seem and seek to define us are, ultimately, fleeting.

Stacy: Jake calls it white noise, but I like to think of it as grey matter and I’d add religion to his mix. There’s plenty out there for us to work from. Art—no matter how political or authoritarian in voice—is left for open interpretation. It can be taken in by its audience and turned into needed, further conversation. As it asks timely, hard questions of us, or just gives us pause or reprieve, it can hold us, nurture us.

Obviously exhibiting artwork physically is on hold, have you any projects or goals you are working towards?

Stacy: Audiences are still there online and will return to physical spaces when the world settles into its new normal. For us, our goal is to work on forgoing the end for now: the expectations to publish, exhibit, etc. We’re determined to support each other’s sanity while structuring more time to focus on our making, our language of dealing.

Stacy: We live in Moscow, Idaho, a small town in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. I’m a mixed-media artist, primarily creating in 3D and an Associate Professor of Art + Design at the University of Idaho with a passion for dancing and 80s power ballads. Jacob, I call him Jake, is a writer I picked up at a bar in town last year.

Jacob: I rarely go to bars anymore, but, when I do, I find myself picked up and pocketed. I graduated from the University of Idaho’s MFA program with a specialty of fiction in 2019. I have a bit of an obsession with the craft of writing, a passion for ice/rock climbing, and a fondness for all -isms, -ists, and manifestos.

How has the pandemic affected you, your artwork and day to day?

Jacob: Honestly, although it feels weird to say aloud, in terms of my writing process, the pandemic has actually been a bit of a blessing in disguise because it’s provided me with ample time to write. After losing my substitute teaching gig due the school closures, I went back to work revising a collection of short stories. I’m so far into the voices, narratives, and ideas in these stories, that they don’t really allow the contemporary me in, so, it’s a bit like time traveling back to a pre-covid reality, which is a nice respite for a few hours each day.

Stacy: I’ve had respite too; I’ve been on sabbatical since January. As a professor, finding any chunk of time for studio is refreshing, so I was sure these five months were to be exponentially more serendipitous. But since covid popped my sabbatical bubble, I’m battling even my sewing machine. Just being near it used to feel soothing, but now whenever I’m not making masks, it guilts me. My creative resolve fractures. I stop making. Attempts at simple productivity while quarantining with Jake—planning meals, exercising, sharing books, etc.—and my week-day calls with my graciously forthright “art accountability buddy,” is helping me reconnect with my elusive sabbatical-self.

Tell us a bit about your work. What themes do you pursue in your work separately?

Stacy: Recently, my solo work has dealt with shifting justifications of our boundaries—both physical and personal—especially as they become distorted or lost. You can see this in works like my mixed-media wall piece series Shedsor my installation Dislocation Shifts. Consumed by modern distractions and environmental losses, so much of our lives seem to rush by, yet there is also an atmospheric desire to ground ourselves. I’m inspired by collapsed architectures, tight living spaces, upholstered furniture and the bits of nature and navigation you can find right outside a home—tree branches, gardens, stones & weeds, welcome mats & sidewalks. I enjoy the strange familiarity and poetic weight of colliding forms to capture complex personal navigations.

Jacob: I like the themes in my work to rise organically from the narrative itself. What really interests me is the reader’s experience, because without a reader a story is inert, lifeless. It is a minor distinction, but one I value highly, that is, I view storytelling not as a means of transmitting a character’s life, or philosophical ideal, or a political message, but as means to engage experientiality within the reader. I believe that even story is secondary to this, that every craft decision must serve not the artificial construct of language & narrative, but the visceral experientiality that language creates within the body and mind of a reader.

How have you changed your working process during the pandemic? What became your method of working together?

Stacy: When I came across the Isolation One Digital Residency with Murze Iso Art Fest, I saw it as a nice distraction from my canceled residency in Macedonia, a way to re-center my creative focus, and an opportunity to work with Jake for the first time: #isolatedbutnotsolitary.

Jacob: For me, writing has always been a solitary act. This was my first collaboration and learning how to let another voice into my practice was a wonderful and challenging experience. It took Stacy hovering over my shoulder and asking “what are you thinking” for the third time for me to realize that I didn’t actually know what I was thinking. That in order for me to express an idea, I need to translate from the discordant ideas, vague images, prosody, and the potentiality of emotion into language. Until that process is complete, I don’t, consciously, know what the hell I’m talking about, and learning to let Stacy into that stage, the intuitive process, felt a bit like having someone stumble around the dark and cluttered crawl space of my unconscious mind. To be honest, it was a bit invigorating.

Stacy: While Jake adapted to collaboration, I dealt with opening up my studio space to someone else. Since the lockdown, I’ve given myself the constraint of working only with the materials already at home or in my studio. Before I invited Jake into my studio, I created a pile of untouchable materials that were off limits. It made me uneasy at first to see him rummaging through parts of previous works. I had to fight my initial “No f’ing way”s and “I can’t use that again”s. It was a bizarre editing process of making do. The lack of familiarity with my work, his fresh eyes, so to speak, offered a potential for reseeing. His new perspectives, and physical presence, defamiliarized my process and allowed space for fresh constructions to begin.

What themes evolved as you began working together?

Jacob: Stacy and I spent a lot of time discussing the rhetoric of Co-vid. We were struck by how, even in a clearly uncertain crisis, people’s responses seemed to be spoken with certainty. They seem to be stockpiling present participles, bombarding us with “ing” words, dwelling on every breach of the new social contract, assuming the role of expert, and even weaponizing shame.

Stacy: Interested in the idea of trying to catalog all these floating yet tangled “ing” words, I began stitching our growing list of weighted words onto light blue sheets for what we are now calling Receptacle (Dwelling). It is a work in progress that will most likely grow into more sets of 3-ring bound word groupings. We also played with other display iterations of text on fabric strips. This process led to the blue spinal form in our installation.

Jacob: Stacy had a simple, free-standing steel frame, about as tall as a door, and just big enough for a person to step through. We shifted cinder blocks, shuffled metal frames, and weaved metal netting made from bed springs around the threshold. Stacy found meaning in the spatiality of the relationship between objects and I built a narrative with them, yet we couldn’t connect with each other’s vantage points. That is, until Stacy referred to the piece as a “persona”, and that’s something I understand, that’s character. I suggested we take a page from Gilbert Sorerentino’s novel Aberration of Starlight. We created a speaker with a series of questions: what they remembered from X event in their life; on what foundational memory was the character’s personality constructed, etc. We constructed our vague persona’s backstory, and suddenly, we had a speaker to contend with knocking at our steel threshold.

Stacy: We returned to physical construction, adding old pointed wood forms from my What Man Builds, Man Can Confuse series. They became the spine, the spewed expectations, and pointed fingers. As a net or cloak or cape or frozen conveyor belt, the metal mesh and blue fabric systematically projected our ideas into space, but now, in sync, the making flowed. We are now calling this installation, Beside the Pointed. We envision it standing among a mass of text imprinted onto the walls around it. Tangled “could”s, “would”s and “should”s, misplaced expectations, will become the atmosphere for what we have now while our Astro-turfed “ing” can act as a ground for more problematic projections to land.

Is there something you couldn't live without in your studio? What is your most essential tool?

Jacob: Solitude and coffee.

Stacy: And lucky for him, I’m here to challenge him on that first one... Without a variety of needles and thread, I’m twitchy.

What do you feel the role of visual artists and writers is in society?

Jacob: I’ve always been partial to Ezra Pound’s idea that the artist is “the antenna of the human race.” Like the chitinous antenna of an ant, I think the artist’s role is to perceive the world without judgment, to try to see the world, not as absurd or systematic, but simply perceive it as it is. To see beyond cultural/political/social white noise, beyond the systems that we inhabit and inhabit us, because, in the end, the contemporary systems that seem and seek to define us are, ultimately, fleeting.

Stacy: Jake calls it white noise, but I like to think of it as grey matter and I’d add religion to his mix. There’s plenty out there for us to work from. Art—no matter how political or authoritarian in voice—is left for open interpretation. It can be taken in by its audience and turned into needed, further conversation. As it asks timely, hard questions of us, or just gives us pause or reprieve, it can hold us, nurture us.

Obviously exhibiting artwork physically is on hold, have you any projects or goals you are working towards?

Stacy: Audiences are still there online and will return to physical spaces when the world settles into its new normal. For us, our goal is to work on forgoing the end for now: the expectations to publish, exhibit, etc. We’re determined to support each other’s sanity while structuring more time to focus on our making, our language of dealing.